Commentary at ISPI, 15 April 2025

As the war in Sudan approaches its two-year anniversary, the conflict is set to enter a new phase. Regaining the heart of the capital Khartoum has been a major success – and a morale booster just ahead of the end of Ramadan – for the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). The Rapid Support Forces (RSF), for their part, still control vast swathes of Sudan’s territory west of the Nile. Military action won’t end the war anytime soon. This could be an entry point for a renewed push for a ceasefire.

Given this prospect, more effective international coordination is essential. There is currently no unified, regular diplomatic contact group on Sudan, the biggest humanitarian crisis in the world with more than 30 million peopleneeding assistance (and much less getting it). The so-called Extended Mechanism created by the African Union (AU) in the first weeks of the war has only met infrequently and is probably also too unwieldy as a workable mechanism. Sudan special envoys have met in various configurations, including convened by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the sub-regional body for the Horn of Africa, and by Ramtane Lamamra, the UN Secretary-General’s Personal Sudan Envoy. However, none of these have yet resulted in a regular mechanism.

An overall aim of such a mechanism should be to provide regular updates of the members’ activities and create a platform to provide a modicum of coordination wherever possible. Ideally, it would also lead to more coherence, unity and sincerity in support of a negotiated end to the war, help mobilizing resources to avert (further) famine, and prevent the polarization of regional and international actors that are increasingly taking sides in the war. However, the current geopolitical context means that these objectives are probably no more than wishful thinking.

Why international efforts to end the war have failed so far

The war in Sudan is becoming increasingly protracted. SAF and RSF lead coalitions of armed actors over which they do not have complete control, but whose interests they have to consider in their political positions. Both Abdelfattah al-Burhan as head of the SAF and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (better known as Hemedti) as head of the RSF made clear in their respective Eid speeches at the end of March 2025 that there would be no negotiations. In contrast to previous declarations by the RSF over their readiness to talks, Hemedti now said there would be “only the language of the gun”. The roadmap for peace published by Sudan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs includes a national dialogue and a cabinet of technocrats, but also makes the laying down of arms and withdrawal from all areas currently controlled by the RSF a prerequisite: a negotiated surrender in all but name.

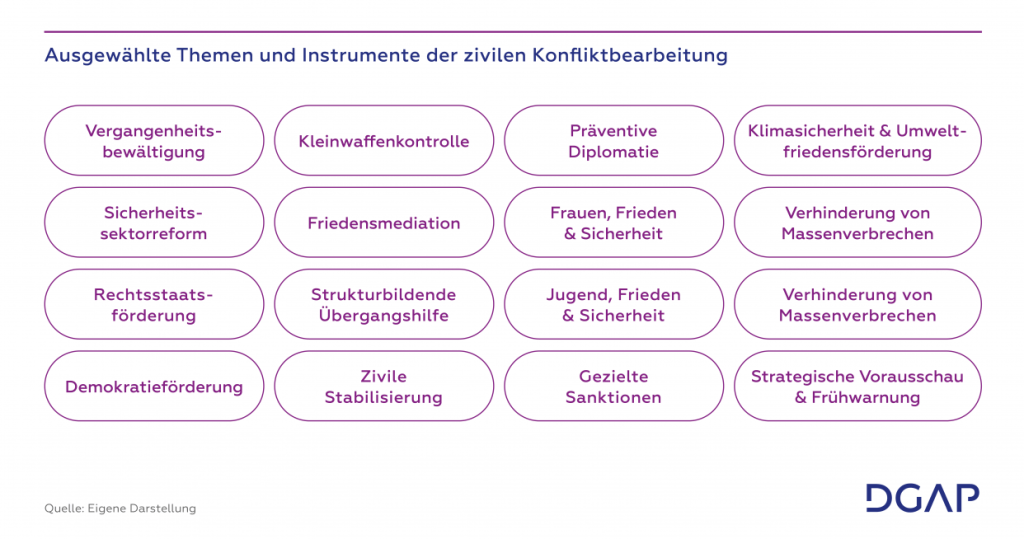

So, there is no easy opening for mediation. In view of these rejections, international efforts so far relied essentially on three different approaches: security talks focused on a ceasefire and protection of civilians; personal accommodation through a face-to-face meeting between al-Burhan and Hemedti; and mobilizing a civilian bloc as alternative “third force”.

Talks in Jeddah led by the US and Saudi Arabia in May 2023 resulted in a declaration on the protection of civiliansand a one-week ceasefire signed by SAF and RSF. Nevertheless, the parties did not adhere to their commitments, with no consequences for them. At the next round in October/November 2023, the parties did not confirm the ceasefire, and failed to follow through on their individual commitments for improved humanitarian access. Instead of a third round, the US tried to convene a slightly broader group of states and the two belligerents in Geneva in August 2024. However, the SAF delegation did not want to be treated on the same level as the RSF (and avoid exposing its internal differences) and declined the invitation. Lowering their ambition, the US-led coalition of facilitators founded in Geneva focused on improving humanitarian access instead. However, these efforts had limited success, as humanitarian access to fighting zones remained severely hampered in their search for a pragmatic approach, the US were prepared to accord the authorities in Port Sudan more legitimacy by treating al-Burhan as Head of the Transitional Sovereign Council and not just as head of the military. The supposed lead mediator, US Special Envoy Thomas Periello, was, for US security reasons, only able to travel to Port Sudan and meet al-Burhan in November 2024 though, when the result of the presidential elections signaled the foreseeable end of his term with the outgoing Biden administration, weakening the scope of this initiative.

AU and IGAD created several mechanisms for mediation, but were not fully accepted by the SAF: firstly, Sudan remains suspended from the AU because of the coup in October 2021; SAF withdrew from the IGAD initiative after a failed one-on-one meeting with Hemedti was followed by Hemedti attending an IGAD summit in Kampala in January 2024. SAF also rejected Kenya’s role as chair of IGAD’s quartet, a skepticism which only grew in light of the founding of a new RSF-led political alliance with Nairobi’s blessing in February 2025. The AU’s high-level panel on Sudan was very slow to organize talks with civilian actors, which has been its main objective, and failed to follow-up with them for months after two roundtables in the summer of 2024. The AU’s presidential ad hoc committee aims to organize a face-to-face meeting between Burhan and Hemedti, but has never met.

Competition between mediators did not help. Egypt distrusts IGAD as a mediation channel – both because it is not a member state, and because of the dominant role played in it by Ethiopia. It pushes for Sudan’s readmission to the AU (so far unsuccessfully) and organized its own initiative of Sudan’s neighboring countries (in July 2023), with no impact. Being non-African, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, major players in Sudan, are not part of the AU, and are also skeptical of pushing for a renewed civilian-led government in Sudan. When the UAE and Egypt facilitated a secret meeting in Bahrain, SAF and RSF both sent their respective deputy leaders and got relatively far. Yes, negotiations stalled again, and SAF withdrew from the talks, pointing to the RSF’s failed commitment to the Jeddah declaration. Cooperation between the AU and UN envoys remains difficult on the Sudan file. So-called “proximity talks” (i.e. indirect) talks set up by UN Special Envoy Ramtane Lamamra did not bring a breakthrough. Finally, a draft resolution in the UN Security Council co-signed by the UK and Sierra Leone, that would have asked the UN Secretary-General to develop a compliance mechanism for the protection of civilians and called for a cessation of hostilities, was vetoed by Russia in November 2024.

The fractured nature of the warring parties has been a major challenge. The mediation efforts failed to sufficiently account for the complex dynamics within the conflict parties as well as between them and their external backers, including in response to the situation on the battlefield. Competition between would-be mediators allowed Sudanese warring parties to decline invitations, withdraw from negotiations, and to avoid making compromises that could fracture their coalitions of militias, regular forces and mercenaries.

Learning from the Friends of Sudan experience

On April 15, 2025, British Foreign Secretary David Lammy is hosting a ministerial conference on Sudan in London, organised with Germany, France and the European Union. Lammy has vowed to make Sudan a foreign policy priority. The conference is billed as a follow-up to a similar conference in Paris a year earlier, which was co-hosted by the EU, France and Germany, all three of which will co-convene the London meeting with the UK as well. In contrast to Paris, there won’t be a humanitarian pledging element, nor will there be a parallel meeting of Sudanese civilian actors. Instead, the UK will convene around 20 foreign ministers and representatives of international organizations. Better coordination among this group is a central objective.

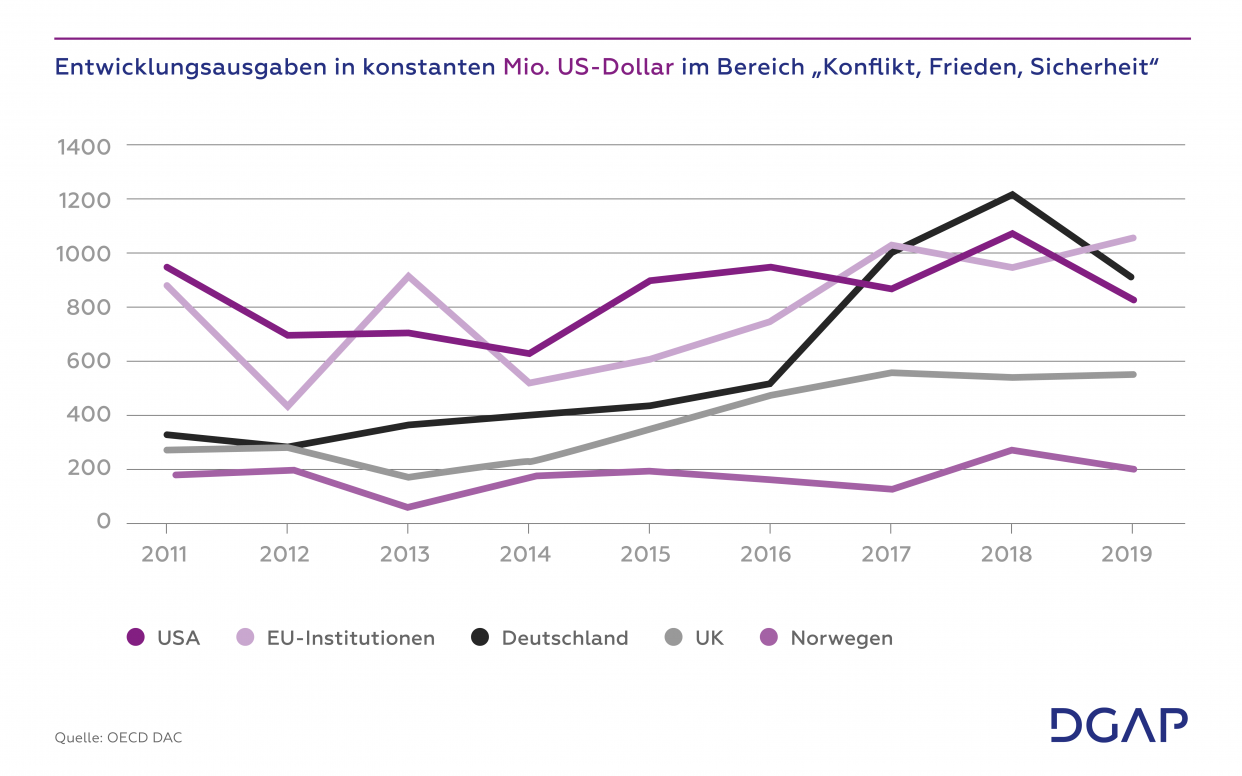

In doing so, the UK should reflect on the experience of previous coordination mechanisms on Sudan. For decades, the UK was itself part of the Troika (with the US and Norway), which supported negotiations to end Sudan’s Second Civil war and South Sudan’s path to independence in 2011, among other issues. However, the Troika doesn’t appear to be an appropriate grouping on Sudan any longer, given the drastic aid cuts by the US and the Trump administration’s disregard for multilateralism and preference of optics over lasting results.

After the fall of Sudan’s thirty-year dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019, the UK was also part of the Friends of Sudan. This was an informal diplomatic group, co-founded by Germany and the US, whose primary purpose was to support Sudan’s transition process. Notably, it included also Egypt, the UAE, Saudi-Arabia, Qatar and the AU, among others. For a while, the Friends of Sudan met regularly at the level of Sudan envoys or senior officials, focusing mainly on coordinating the economic and financial support to the transitional government, including debt relief and setting up a cash transfer program for the parts of the population hit hard by the withdrawal of subsidies and high inflation. After the coup in October 2021, it lost its civilian Sudanese counterpart, and it petered out once the war started and the Sudanese authorities pushed out the UN mission – which had taken over a regular convening role of the Friends of Sudan – a few months later.

Key issues going forward

None of the mediation initiatives so far did have any major impact. Four points will be critical if any new diplomatic coordination mechanism is to even have the chance to influence events in Sudan.

First, any high-profile conference on Sudan needs to have a link to Sudanese civilian actors. UK diplomats held meetings with Sudanese civil society in the Horn of Africa and the British Director General of African Affairs spoke with the authorities in Port Sudan to collect their perspectives. Still, Sudanese will always question the legitimacy of an international Sudan conference without any Sudanese present. The Paris conference organized a roundtable of around 50 people that represented different types of stakeholders, not just one civilian coalition. Attendees told me that they found it useful, because it had been rare for those diverse perspectives to be in the same room since the start of the war.

Second, any coordination mechanism resulting from the London conference should be nimble and relatively informal. There needs to be some agreement on who to include and how frequently to convene them, but perhaps not much more. It is unlikely to develop strong agency for joint actions. The main multilateral organizations – the UN, the AU, IGAD, perhaps the EU – should be in the lead, if they can be made to act jointly. Like-minded actors need to focus on tangible support to the Sudanese population, especially in light of the massive aid cuts by the US and other countries. While they won’t be able to fill all gaps, they should concentrate on stepping in to fully support the appeal of the Emergency Response Rooms, mutual aid networks. To function, this initiative would need 12 m USD per month, hardly any of which they have received so far. This won’t be enough – the UN appeals for Sudan and the neighboring countries are around 6 bn USD for 2025 – but the ERRs work particularly in areas hardly reached by international aid, where the risk of starvation is among the greatest.

Third, a new diplomatic group as well as the London conference should refrain from normalizing external interference. The Paris conference included a joint communiqué that urged “all foreign actors to cease providing armed support or materiel to the warring parties”. Egypt and the UAE signed this statement – yet, they have continued their support to SAF and RSF. If they were able to sign onto a similar statement, they could do so confident that a lack of commitment would remain without consequences. The foreign ministers present at the meeting should hold these foreign sponsors accountable for supporting warring parties. They should single out the UAE in particular because of their support to the RSF, as described by U.S. Senator Chris Van Hollen and Representative Sara Jacobs, citing a US government briefing. Just this weekend, the RSF captured Zam-Zam camp, Sudan’s biggest displacement camp, after besieging it and neighbouring El-Fasher for many months. The RSF operates advanced drones and artillery to attack El-Fasher and Zam-Zam camp, which it most likely acquired from abroad.

Finally, those international actors that have not picked a side in Sudan’s devastating civil war should not do so now. Normalizing relations with SAF-led authorities in Port Sudan won’t help people trapped in RSF-held areas nor will it help end the war. Assembling in London, foreign ministers will call global attention to the catastrophe that is the war in Sudan. Outrage without any of these actions would just underline their collective weakness. It is time to take responsibility.