An independent inquiry into the UN system’s response to the mass violence against the Rohingya population in Myanmar found “systemic and structural failures”, echoing an earlier finding of a similar investigation on Sri Lanka. At the same time, the inquiry conducted by former Guatemalan diplomat Gert Rosenthal leaves important questions unexplored. Crucially, Rosenthal did not explore allegations that the UN Country Team in Myanmar was complicit in the regime’s discrimination against the Rohingya population. For the UN to learn from the past, it needs to have a more detailed record of the decisions taken.

This text first appeared on medium.com on 15 September 2019.

Learning lessons from past mistakes is important. That is true both on an individual level as well at the level of the United Nations. Rwanda, Srebrenica, Sri Lanka, Haiti, South Sudan: there have been many independent inquiries into the UN’s actions in a situation where serious human rights violations took place. They have spurred influential, albeit imperfect reform processes of the organization’s institutional architecture, processes and policies. Unfortunately, the latest such report, into the UN system’s response to the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar between 2010 and 2018, is too shallow and generic to allow for substantial learning to take place how the UN system could have used potential leverage to prevent the atrocities. It also fails to investigate allegations of the UN’s complicity in the systemic discrimination of the Rohingya population that are already part of the public record.

The Rohingya people have suffered

from systemic discrimination by the Myanmar government for decades. In a

Buddhist-dominated country, the government and many Buddhist citizens regard

the Rohingya as foreign, rejecting even their name and calling them “Bengali”,

i.e. belonging to neighboring Bangladesh. The Rohingya have lacked citizenship

and associated rights since the 1982 nationality law. Amid the democratic

reform process in Myanmar since 2012, discrimination against the Rohingya has

increased, including restrictions on their freedom of movement. In reaction to an

attack on police stations by a Rohingya armed group in August 2017, the Myanmar

security forces engaged in indiscriminate violence against the

civilian population, killing thousands and driving around 700,000 people across

the border into Bangladesh. Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid

Ra’ad al-Hussein described these attacks as “textbook example

of ethnic cleansing”. A fact-finding mission recommended that senior military commanders

should be investigated for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. It

found six indicators of “genocidal intent”, including in its most recent report

evidence of sexual violence by the security forces,

with hundreds of women and girls gang-raped.

Existing allegations: timidity or even complicity?

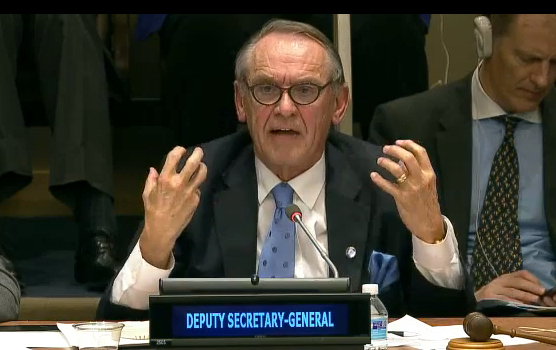

For several years, there have been

serious allegations of misconduct by the UN Country Team based in Myanmar and

senior UN officials elsewhere, including through leaked internal reports,

statements by former employees, and investigative reporting. These allegations

are complex, but essentially fall into either of two main points. The first

concerns a lack of coherence both within the UN presence in Myanmar and among

the UN leadership in New York. Even though the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

and his deputy Jan Eliasson had spearheaded a reform to improve the UN system’s

processes and internal mechanisms in the wake of the Sri Lanka inquiry, these

reforms were not effective in Myanmar. Specifically, public reports charged

that the Resident Coordinator, the highest UN official in the country, excluded critical voices from meetings and suppressed a report warning of a deterioration

of the situation in early 2017. Mirroring differences between public advocacy

and quiet dialogue at the country level, senior UN officials disagreed on the organization’s overall

approach, with Eliasson and al-Hussein on one side, and the head of the UN

Development Programme, Helen Clark, and Vijay Nambiar, special advisor for

Myanmar, on the other side. Limited public or private criticism by the UN after

an earlier massacre, “proved to the Myanmar government that it could manipulate

the U.N.’s self-inflicted paralysis in Rakhine”, a UN official told the journalist Column Lynch. In other words, the

activists allege that contradictory messages from different parts of the UN

system and relative muteness on major human rights issues signaled to Myanmar’s

security forces that it could get away with them.

The second point that those reports

make goes even further. They allege that the UN Country Team was complicit in

the discriminatory policies of the Myanmar government towards the Rohingya

people. The UN and its international partners sustained displaced Rohingyas in

internment camps, which the government did not allow them to leave, and

collaborated with the government in the so-called Rakhine Action Plan. The plan,

supposedly aimed at improving the humanitarian situation, included the registration of Rohingya as “Bengalis”,

thus erasing their identity. Liam Mahony, an international consultant, spoke

with representatives of the humanitarian community in Myanmar and observed in a

critical report in 2015: “The State benefits not only from having the cost of

minimally sustaining the population carried by others, it also gets a

legitimacy benefit from having all these international organizations present

(and better yet, present and quiet.)”

Explaining “systemic failure”

In his report, Gert Rosenthal largely confirms the first

allegation, and ignores the second one. He identifies the tension between quiet

diplomacy and public advocacy as the core challenge for the UN in dealing with

the situation in Rakhine state, and “systemic and structural failures” in

resolving them. In a chapter of just six pages, Rosenthal describes five

reasons for these failures: lack of support from member states; the absence of

a common strategy by the UN leadership; too many points of coordination; a

dysfunctional country team led by a Resident Coordinator out of her depth but

unable to receive more expert support from headquarters because of government

opposition; and competing lines of reporting from the field, muddling

information and analysis available in New York. Because the problems were

systemic, no single entity or individual should be singled out, he concludes,

pointing to the “shared responsibility on the part of all parties involved”.

The report’s observations are

pertinent, and in mentioning the lack of executive decision-making by the Secretary-General go beyond

the findings of the Sri Lanka inquiry that was published in 2012. As a new generation of UN

Country Teams has started to deploy since the start of the year, extracting

lessons for their engagement would be important. Rosenthal acknowledges that

pushing for change in the government of Myanmar’s behavior towards the Rohingya

while simultaneously working with it on humanitarian and development issues as

well as supporting the democratic transition process was “a difficult balancing

act”.

Diplomacy on human rights issues

often involves such balancing acts for the UN. The restrictions present in

Myanmar – a repressive government, divided member states, and lack of dedicated

UN capacities on political and human rights issues – were not unheard of. The

Resident Coordinator was in a very difficult position to engage in advocacy, as

Mahony had already concluded in 2015: humanitarian organizations were

“expecting UNHCR and the Resident Coordinator to do it all for them.” Yet it is

difficult to conclude from Rosenthal’s synoptic account which kind of advocacy

and at what points in time could have been successful in dissuading the

security forces from their attacks.

Lack of detail, counterfactuals and potential leverage

A detailed narrative investigating

incidents where the UN was faced with a concrete incident and needed to make a

choice between advocacy and diplomacy would have been helpful. Which

information did which UN entity have, how was it handled within the system, and

who used it in which form in any engagement with the government? In which ways

did the actions of the government, member states and the UN entities interact

to inform decision-making in the UN Country Team and at UN headquarters? For

example, the journalist and Myanmar expert Francis Wade writes about the way in which an incident in the

village of Du Chee Yar Tan had instilled greater caution in the UN’s advocacy.

Based on initial reports of a massacre, the UN had raised the issue with the

government authorities, only to be rebuked and find out later from further

sources that the alleged incident was apparently not as serious as initially

assumed.

Closer attention to such incidents

would have been important. But Rosenthal had very limited capacity, having to

work on its own without support staff or colleagues. He did not travel to

Myanmar. Investigating inflection points would have helped to persuade the

reader of his conclusions. It would have also allowed to point out more

counterfactual decisions, or the consequences of the choices that were made for

the calculus of the security forces and for how events unfolded on the ground.

The only benchmark that Rosenthal mentions is an observer mission in Rakhine

state that could have monitored the actions of armed groups and the military.

Such a mission could have investigated incidents such as the attacks on police

stations in 2016 and 2017 that provided the excuse for the security services’

“clearance operations”. But, as he himself acknowledges, such a mission was

impossible without the agreement of the government.

Lastly, Rosenthal hardly enquires

into the potential leverage of the UN system, or any other actor to change the

government’s behavior. He briefly mentions China, India, Indonesia and ASEAN as

“privileged” partners of the UN, but does not discuss any specific efforts UN

officials made to convince them to put pressure on the government, including

for the failed upgrade of the UN presence in the country. Nor does he inquire

whether the US gave in too quickly to Chinese opposition to dealing with

Myanmar in the UN Security Council earlier on. Rosenthal observes that even when

Guterres wrote a stern letter to the Security Council in

early September 2017 after the start of the ethnic cleansing campaign, it did

not lead the council “to respond in either a forceful or a timely manner.”

In contrast, Mahony’s 2015

assessment talks of the “uniquely privileged position” of the UN and member

states in relation to a government that desperately sought international

legitimacy for its democratic reform process and the “huge financial rewards

that this new leadership brings”. It would have been essential to learn if UN

actors felt the same and in what ways they used such leverage.

Why accountability matters

The shortcomings of such an internal

review matter. Not only does the UN owe greater accountability to the Rohingya

victims of the systemic discrimination, forced displacement, and indiscriminate

killings, but also to its own staff, and to the wider public. The Secretary

General’s Office is currently leading a follow-up process to the Rosenthal

report. Its first task will need to be to expand on Rosenthal’s very short

recommendations.

Even though Rosenthal does not say

so explicitly, some commentators have drawn the conclusion that his report “assigns

collective responsibility for the atrocities committed during the 2017 Rohingya

crisis to both the UN civil service and UN member states.“ That is

misleading – there is nothing in the report to suggest how a more coherent UN

system supported by member states could have prevented the atrocities. Maybe

more pressure could have emboldened the civilian government led by Aung San Suu Kyi to try and

stand up to the military, or earlier and more widespread targeted sanctions

could have influenced the military leadership. Without a more thorough analysis

of international engagement, we can only guess.

In the meantime, the UN’s reputation further deteriorates, potentially undermining its work elsewhere as well as the reform of the country team system. No official, diplomat, or government representative has been held accountable for a responsibility that is shared collectively. More than one million Rohingya refugees continue to live in horrid conditions in Bangladeshi refugee camps.