This post appeared on the Blog Junge UN-Forschung.

They had expected it anxiously. When I spoke with the UN officials working on the Secretary General’s Human Rights Up Front initiative last year, they were concerned the internal initiative could become intertwined in the polarized debates between UN member states on the role of human rights in the organization. The UN Secretary-General launched the initiative in 2013, with the aim to raise the profile of human rights in the work of the whole UN system. As a reaction to a devastating internal review panel report on the UN’s actions in Sri Lanka, the initiative includes a detailed action plan to improve the mechanisms for raising serious human rights violations with member states, for internal crisis coordination, and information management regarding such violations. The UN officials – rightly – felt that the new engagement of the UN system with member states that the initiative entailed had to build on its two other elements: cultural and operational change within the UN system, i.e. coherence between the development, peace and security and human rights arms of the UN.

As I argued in my policy paper published last July, Human Rights Up Front could not remain a pure UN matter; to be successful in the mid- to long-term, member states need to endorse it wholeheartedly. This includes an increased funding for the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and an intergovernmental mandate for a more political role of UN Country Teams. In a letter on Christmas Eve 2015, the Secretary-General officially recognized the crucial role of member states: “While the Initiative is internal, its objectives speak to the purposes of the whole United Nations and will be greatly enhanced by support from Member States.”

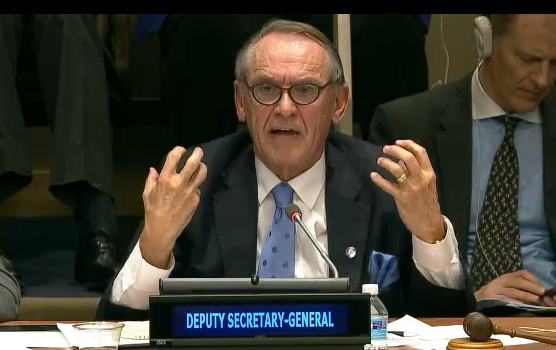

On 27 January 2016, Deputy Secretary-General Jan Eliasson briefed the General Assembly on the initiative’s implementation since its inception more than two years ago. The broad support he received from the member states present holds five important lessons for selling UN human rights diplomacy more generally.

First, open consultations facilitate trust and transparancy. Many of the 22 member states and one regional organization (EU) that spoke during the informal briefing session, expressively welcomed the opportunity for open dialogue itself. While Eliasson had briefed member states twice before (in New York and Geneva) on Human Rights Up Front, and both he and Ban Ki-Moon referred to it in their speeches, the interactive session provided an opportunity to take stock with member states.

Second, take on board your critics. In reaction to previous comments from member states, Eliasson explicitly referred to the relevance of social, economic and cultural rights violations as precursors to physical violence and instability. China’s and Nigeria’s inputs duly acknowledged the importance of development for prevention.

Third, universality. The delegate from Iran asked how the UN could adequately respond to human rights violations in the Global North such as increasing xenophobia when most of its offices were in developing countries – a longstanding criticism in UN human rights forums. Eliasson emphasized the comprehensive reach of the early warning and coordination mechanisms, and compared it to the successful example of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in the Human Rights Council, which commits every UN member state to a thorough peer-review of its human rights record. Indeed, the regional quarterly reviews, a new early warning and coordination mechanism introduced as part of Human Rights Up Front, look at all world regions. These coordination meetings bring together officials from divergent UN agencies to review adequacy of the UN’s response to potential risks for serious human rights violations.

Forth, association with existing mandates and agendas. Whenever the UN secretariat comes up with its own initiatives, it creates certain anxieties among member states eager to control the international bureaucracy. It was a sign of the Deputy Secretary-General’s successful outreach that no member state questioned the initiative and the role of the secretariat in coming up with it per se. In addition, Eliasson had his staff compile a list of the Charter provisions, treaties and resolutions by the General Assembly and the Security Council relevant to conflict prevention and human rights diplomacy. Responding to calls to do so for example by China, he also welcomed the role of conflict prevention as part of agenda 2030, in particular its goal 16.

Fifth, personal experience and credibility. Human Rights Up Front’s outreach benefits tremendously from having DSG Eliasson as champion in the secretariat. Not only did he conduct several mediation efforts himself, he was part of key normative and operative developments in the United Nations in the past twenty years that pertain to the Human Rights Up Front agenda. As first Emergency Relief Coordinator of the United Nations, he saw at first hand the resulting coordination challenges for the newly created position of humanitarian coordinators, a task usually taken up by the existing resident coordinator and resident representative of UNDP. In 2005, he presided over the record-breaking World Summit as president of the General Assembly, which endorsed the notion of a responsibility to protect populations from mass atrocity crimes, and agreed on the establishment of the Human Rights Council and Peacebuilding Commission. Under his leadership, the General Assembly later agreed on the details of the Human Rights Council, including the UPR. All of this provides Eliasson with unrivaled credibility among member states; his diplomatic skills enable him to put this status into practice.

The overwhelmingly positive welcome in the General Assembly session should not disregard the fair and important questions that even constructive member states still have. Several representatives such as Australia and Argentina asked for concrete examples of the initiative’s implementation, and China wanted to know which experiences the Secretariat had made in the first two years of the action plan’s implementation. While much of the high diplomacy of the UN may be sensitive and should remain confidential for the time being, there is no reason why the UN could not report on efforts taken after the fact, in consultation with the country concerned. After all, OHCHR reports annually about its activities including on a country basis, as do other UN entities. Indeed, three UN officials wrote a blog entry for UNDG how Human Rights up Front had helped them in following up on Argentina’s pledges under the UPR mechanism.

Finally, the UN leadership should not shy away from calling remaining challenges within the UN system by their name. It is understandable that Eliasson and others prefer to stress how “enthusiastic” staff members have greeted the initiative. Yet the action plan has also included new tasks for OCHR, without generating new funding. The creation of a common information system on serious human rights violations was hampered by different understandings of the objectives of protection and varying standards for the protection of victims and witnesses of violations. The new universal human rights training for all UN staff was seen as ineffective and beside the point by a number of observers within the UN system. Most troublingly, an independent expert panel on sexual abuse and exploitation in UN peace operations pointed to „gross institutional failure“ in the UN system, exposing a serious deficit in the organization’s internal culture (Eliasson has, in fact, made the link with Human Rights Up Front at a press conference). If Human Rights Up Front is to gain more traction with member states, Eliasson and his team should confront these challenges head-on.